Introduction

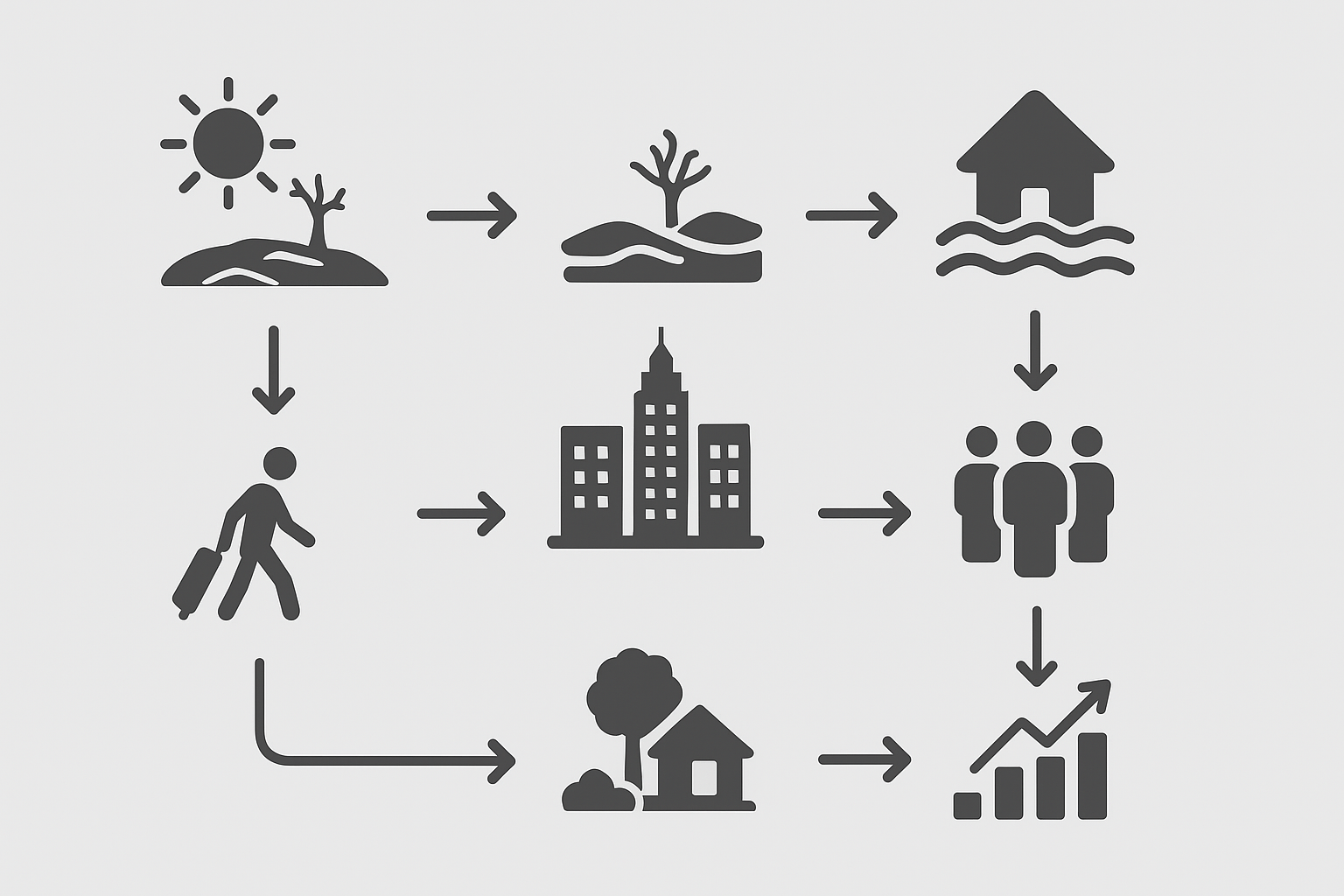

Climate migration is a phenomenon that is becoming increasingly important in public debate and international politics every year. Climate change – such as rising sea levels, increasing droughts, floods, hurricanes and soil degradation – directly affects the living conditions of millions of people around the world. As a result, more and more communities are being forced to leave their homes, whether in search of safety or better living and working conditions.

Climate migration can be both internal, when people move within their own country, and international, leading to the crossing of national borders. This poses serious political, economic and social challenges. Countries receiving migrants must address issues of integration, access to public resources and services, and social tensions. In turn, the countries most vulnerable to the effects of climate change are increasingly calling for solidarity and support from the international community.

In this context, climate migration not only changes the map of human displacement, but also affects international relations. It can lead to new forms of cooperation between countries, but also to conflicts over resources, borders and responsibility for the effects of global warming. Understanding this phenomenon is crucial for developing effective adaptation strategies, migration policies and climate protection measures.

Causes of climate migration

- Rising sea and ocean levels – threatening to flood low-lying areas (e.g. Bangladesh, the Maldives, Kiribati, parts of the US and European coastlines). People will be forced to move inland, which may put pressure on resources in host regions.

- Extreme weather events – hurricanes, floods, fires and droughts – lead to infrastructure damage and loss of homes. Over time, many of these become permanent displacements if reconstruction at the disaster site proves impossible or too costly.

- Environmental degradation and desertification – Drying rivers, lakes and groundwater resources are forcing people to migrate in search of water sources. This is particularly true in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia, where water and fertile soil are scarce.

- Conflicts over resources – reduced availability of water and food increases the risk of local and regional tensions. An increase in the number of ‘climate refugees’ may place a strain on the political and economic systems of host countries.

- Decline in food production – Climate change affects crop yields (droughts, heat waves, new plant diseases). Migration will increasingly be motivated by the inability to make a living from agriculture.

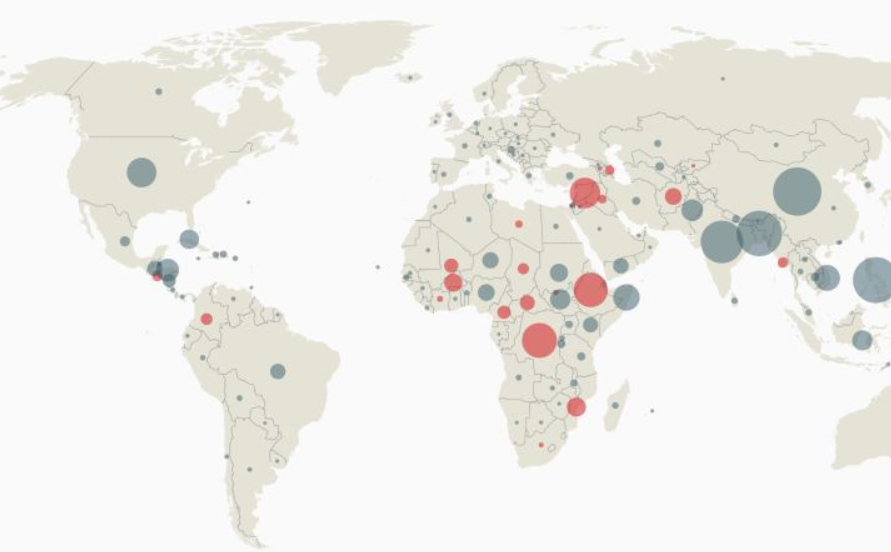

The scale of the phenomenon

According to estimates by the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), up to 200–250 million people may be forced to migrate for climate reasons by 2050.

We are already seeing internal displacement (e.g. in South Asia following monsoon floods) and the first cases of ‘climate refugees’ seeking protection in other countries.

Implications for international relations

Migration can cause social tensions in host countries, as well as conflicts between countries over responsibility and costs. Joint action within the UN, the African Union or the EU will be necessary to develop mechanisms to protect climate-displaced persons.

The importance of transferring financial resources and technology from rich countries to countries particularly vulnerable to climate change will grow.

Possible scenarios

- Cooperative scenario – developing global solidarity, creating safe migration routes and relocation programmes.

- Conflict scenario – rise of nationalism and closing of borders, which may lead to destabilisation of entire regions (e.g. in Africa, South Asia).

- Adaptation scenario – investments in infrastructure and climate adaptation in vulnerable countries to minimise the need for migration.

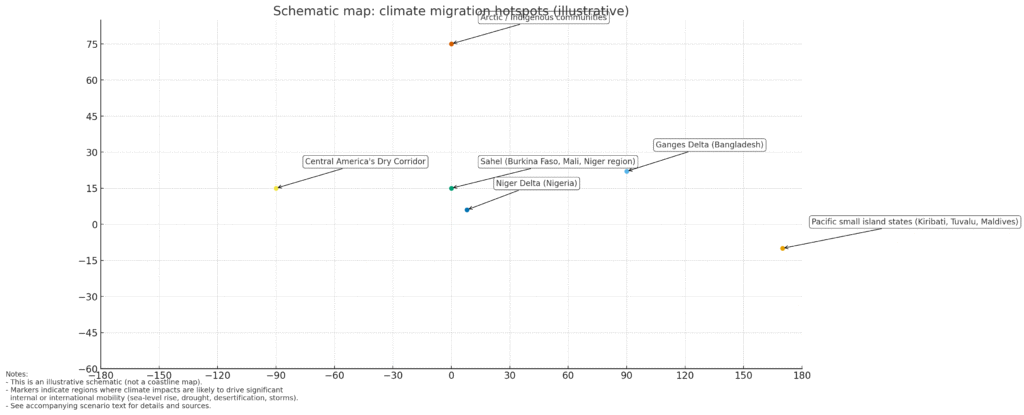

The most vulnerable regions

- Pacific Islands and Small Island States

- Gradual submersion and saline intrusion of groundwater — problems with available fresh water and agriculture.

- Internal relocation (often to capital cities), migration to Australia, New Zealand, the USA or neighbouring countries.

- Partial or total loss of territory may force permanent relocation of entire communities.

- Ganges Delta (Bangladesh), river plains of South Asia

- Floods, storms, sea level rise, coastal erosion.

- Migration to cities (Dhaka, Kolkata), emigration to Gulf countries and beyond.

- High population density — millions of people are vulnerable to cyclical displacement.

- The Sahel and North Africa (e.g. Burkina Faso, Mali, parts of Nigeria)

- Desertification, droughts, loss of fertile land, conflicts over feed and water.

- Internal migration to cities, cross-border flows in West Africa; also the route to Europe (via Libya).

- The combination of environmental degradation and political instability increases the risk of long-term migration.

- Central America and Mexico (the so-called Dry Corridor)

- Recurring droughts, crop losses, intensified hurricanes.

- Migration to cities, emigration to the USA. Intensification of ‘economic migration’ combined with humanitarian crises.

- Coastal regions and deltas in sub-Saharan Africa

- Rising sea levels, coastal erosion, flooding of agricultural land.

- Migration to larger urban centres, pressure on urban infrastructure.

- Arctic and sub-Arctic regions

- Ice melting, coastal erosion, loss of fishing grounds and traditional livelihoods of indigenous communities.

- Local displacement, changes in the economy.

Scale and projections

Estimates vary — the IOM and other sources cite a range from tens of millions to hundreds of millions of people at risk of climate migration by the middle of the 21st century; at the same time, many studies emphasise that most displacements today are internal displacements caused by disasters and degradation, rather than classic migration between countries.

What can be done?

- UN / UNFCCC / international institutions

- Rapid launch and transparent management of the Loss & Damage fund.

- Promotion of international definitions and standards for the protection of climate-displaced persons.

- European Union

- Support for adaptation in transit regions (Sahel, North Africa, Central America).

- Creation of legal migration channels and integration programmes for arrivals.

- Poland and countries of similar size

- Cooperation within the EU and UN: financial support for adaptation programmes, participation in relocations in the region.

- Preparation of a national strategy: reception planning, migration integration, protection of infrastructure against extreme weather conditions.

- Support for development projects ‘at source’: water, agricultural and urban projects.

- Civil society and the private sector

- Participation in rapid humanitarian response, CSR investments in adaptation, technology transfer.

General principles

Global projections of internal displacement due to climate change range from tens to ~200 million people by 2050, depending on the methodology and emission scenario (the World Bank/IOM cite figures of 143–216 million internal migrants; other citations refer to a wide range of up to ~200 million).

The IPCC emphasises that the increase in displacement depends heavily on the level of adaptation, migration policies and socio-economic development — not just on the physical impact of climate change itself.

Risks and ways to minimise them

- Political risk (withdrawal of donors): secure long-term funding mechanisms and diversify sources (public, private, philanthropy).

- Socio-economic risk (integration tensions): invest in integration and education programmes, promote local benefits of migration (labour markets).

- Legal risk (lack of international protection): work on new standards for international protection or regional legal frameworks.

Impact on culture and identity

The loss of land means not only a change of residence, but also the breakdown of communities, languages and traditions.

The inhabitants of Kiribati and Tuvalu are negotiating the possibility of relocating entire communities to other countries — but this raises questions about maintaining citizenship and the sovereignty of a ‘state without territory’.

Resettlement can lead to the formation of diasporas that will fight to preserve their culture and identity outside their former territory.

Legal aspects

Current refugee law (the 1951 Geneva Convention) does not recognise climate refugees — protection is only granted to victims of political or ethnic persecution, etc.

There are ongoing debates about creating a new legal status, but countries are afraid of opening a ‘Pandora’s box’ that could mean having to accept millions of people.

Security and the military

The US military and NATO already treat climate change as a ‘multiplier of threats’ because climate migration can cause instability and conflicts over resources.

In the Sahel, drought and desertification have exacerbated conflicts between herders and farmers, which, combined with the presence of armed groups, has led to an escalation of violence and displacement.

Armed forces are increasingly involved in humanitarian operations following disasters (e.g. the US and Japan after the tsunami, France in Africa), but also in protecting borders against uncontrolled population movements.

Instead of supporting adaptation, some countries may focus on strengthening their borders and military forces, which risks exacerbating international tensions.

The economics of climate migration

Climate migrants are not always a ‘burden’. They can fill gaps in labour markets (e.g. in agriculture, care, construction).

Remittances from migrants to their families in their countries of origin are becoming one of the most important sources of livelihood and adaptation.

Not everyone can afford to migrate. The poorest groups are often “trapped” in the most vulnerable areas, with no means of escape.

Adaptation costs vs. migration costs: The World Bank emphasises that investments in local adaptation are usually cheaper than responding to mass migration later on.

Technology and adaptation instead of resettlement

Protective infrastructure: flood walls, water retention systems, green roofs, erosion-resistant agricultural terraces.

New urban concepts: floating cities (projects in the Netherlands and Indonesia), ‘sponge cities’ in China that absorb excess water.

Agricultural technologies: drought-resistant plants, smart irrigation systems.

Energy and resources: the development of renewable energy sources and seawater desalination reduces the risk of ‘resource wars’.

Limitations: technology is not always available to the poorest communities, which raises the question of global climate justice.

Some communities prefer to stay and adapt rather than migrate, which shows that not all ‘exposure to risk’ necessarily leads to displacement.

Cities as ‘migration magnets’

Faced with the degradation of rural areas, people are increasingly moving to large cities. This could lead to the emergence of so-called climate megacities, where rapidly growing populations will put pressure on infrastructure, housing and public services.

This can result in overpopulation, problems with transport, access to water or energy, and a deterioration in quality of life.

Invisible migrations

These are not always dramatic escapes – often people migrate slowly and quietly: young people leave their home villages to find better conditions in other regions. In this way, entire communities can gradually disappear.

The gradual outflow of residents leads to the depopulation of local communities, the decline of local culture and difficulties in maintaining basic services in rural areas.

Different impacts on different social groups

The effects of climate migration are not the same for everyone. The most vulnerable are poorer groups, who have the fewest resources to protect themselves from the effects of environmental degradation or to relocate to safer places.

However, wealthier people can also suffer losses – for example, owners of luxury seaside properties exposed to rising sea levels, or residents of regions affected by fires or droughts.

Global esteem

By 2050, the number of people forced to relocate due to climate change could reach 200–300 million.

South and South-East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and low-lying islands in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are most at risk.

Psychology and social adaptation

Climate migration affects mental health: stress related to losing one’s home, job, and community.

People displaced to new places may experience post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), especially after natural disasters such as floods or hurricanes.

Displaced communities must reconstruct their identity and social ties, which sometimes leads to local conflicts or alienation.

Integration programmes should include not only housing and employment, but also psychological support and community building; social initiatives that support cultural and social integration, such as neighbourhood clubs and joint activity workshops.

They should also include training for local services and non-governmental organisations to recognise signs of stress and trauma in migrants.

Cities and urbanisation

Many climate migrants end up in cities, putting pressure on infrastructure:

- Transport – a larger population requires the expansion of public transport, roads and cycling systems.

- Housing – there is a growing demand for cheap and accessible housing, which can lead to the growth of slums if spatial planning does not keep pace.

- Public services – schools, hospitals and water supply systems must meet new needs.

This creates an opportunity for the development of climate-resilient cities that are planned with new population inflows and sustainable infrastructure in mind.

Dependence on global supply chains

Climate migration affects food and raw material production.

- Example: droughts in the Sahel and Central America reduce agricultural production, which affects global prices and food security.

Countries receiving migrants can thus protect their supply chains by investing in adaptation at source.

Practical activities:

- International cooperation at the level of global supply chains, e.g. through shared food warehouses and crisis prediction systems.

- Investments in climate-resilient agricultural technologies, e.g. drip irrigation, hybrid seeds and soil monitoring systems.

Digital technologies and mobility

Big data, satellites and AI make it possible to predict migration and plan for the reception of people in less vulnerable cities or regions.

Mobile and blockchain technologies can support secure money transfers, document registration, and access to services for displaced persons.

Examples of applications:

- Satellites monitoring droughts and floods can alert authorities to the need for evacuation and resource allocation.

- Mobile applications for migrants can indicate available housing, jobs, or assistance centres.

- Blockchain can protect the identity documents of displaced persons, which is crucial when moving between countries.

Sustainable diaspora

Climate migrants can form diasporas that support adaptation in their countries of origin through remittances and knowledge transfer.

This provides an opportunity to strengthen local resilience and reduce migration pressure in the long term.

Long-term effect:

- Strengthening local resilience to climate change and reducing forced migration in the future.

- Creating international support networks that connect migrants and their countries of origin in development projects.

Cross-border migration

In some cases, climate change causes international migration.

- Island nations (e.g. the Maldives, Tuvalu) may be partially or completely flooded, forcing residents to seek new places to live abroad.

- Floods in South Asia (Bangladesh, India) and droughts in sub-Saharan Africa are causing migration to neighbouring countries or to larger cities within the country.

- Such migration is often unregulated, and those who move become ‘climate refugees,’ not always protected by international law.

Social and economic impacts

Migration caused by climate change has complex effects:

- Depopulation of rural areas → lack of labour in agriculture, closure of schools, decline of the local economy and services.

- Social inequalities → the wealthy can move to safer places or secure their property, while the poor have limited opportunities to protect themselves from the effects of climate change.

- Pressure on cities → rising costs of housing, transport, education and healthcare.

Demographic changes

Climate change also affects the demographic structure:

- Ageing of rural areas – young people are leaving rural areas in search of work and better living conditions, leaving behind older residents.

- Concentration of young people in cities – this puts pressure on housing, schools, universities and workplaces.

- Change in local culture – migration causes traditional communities and customs to disappear in depopulating regions.

Climate migration and food security

Droughts, floods, hurricanes and soil erosion limit agricultural production and fishing.

Decreased local food availability, rising prices, malnutrition, migration of farmers to cities or abroad.

Solution: Implementing climate-resilient agriculture, building food storage and emergency transport systems, and providing support for displaced farmers.

Urbanisation and climate change

Inflow of people from rural areas affected by droughts, floods or fires.

Overloading of urban infrastructure, increased pollution and CO₂ emissions, rising living costs, transport and water access problems.

Solution: Spatial planning that takes into account the development of new housing estates, investment in public transport, energy networks resistant to extreme conditions, and the development of green infrastructure.

Climate migration and social inequality

Climate change affects poorer communities the most, as they have limited resources for adaptation.

The wealthy protect their assets and can move to safer areas, while the poor remain vulnerable, creating social and economic inequalities.

Solution: Support programmes for low-income individuals, access to climate insurance, creation of affordable disaster-resistant housing, integration of displaced persons.

The impact of climate change on the migration of children and young people

Loss of homes and schools, lack of jobs for parents, economic pressure.

Interruptions in education, health and mental health risks, migration to cities or other countries in search of better living conditions.

Solution: Creating mobile schools and educational programmes for displaced persons, psychological support, ensuring the safety of children in new environments.

Climate migration and local conflicts

Competition for limited natural resources such as water, arable land or pastures.

Social tensions, conflicts between immigrant and local communities, increased crime or violence.

Solution: Social mediation, creation of resource distribution mechanisms, development of infrastructure securing access to water and energy, social education.

Climate migration and critical infrastructure

Floods, hurricanes and fires destroy transport, energy and water supply networks.

Disruptions in energy and water supply, restrictions on transport, difficulties in providing medical services.

Solution: Modernisation of infrastructure, introduction of systems resistant to extreme conditions, emergency planning, crisis storage facilities, development of local renewable energy.

Climate migration and health protection

Climate change increases the risk of infectious diseases, strokes, and water- and air-borne diseases.

Overburdened healthcare systems in cities receiving displaced persons, increased healthcare costs, health problems among displaced children and the elderly.

Solution: Expansion of healthcare systems, mobile clinics, vaccination programmes, epidemic monitoring and health education.

Climate migration and housing policy

The influx of people into cities causes housing shortages and price increases.

The emergence of slums, overloaded urban infrastructure, pressure on suburban development.

Solution: Construction of affordable housing resistant to extreme conditions, revitalisation of abandoned areas, urban planning that takes into account population influx.

Migracja klimatyczna a gospodarka:

Local

Depopulation of rural areas and agricultural regions, migration to cities.

Decline in local production, business closures, pressure on urban labour markets, rise in unemployment.

Solution: Job creation in new settlement regions, support for local entrepreneurship, development of climate-resilient sectors (renewable energy, adaptation technologies).

Global

Climate disasters disrupt supply chains and destroy local agriculture and industry.

Rising commodity prices, global food shortages, migration pressure between countries.

Solution: Diversification of supply sources, climate insurance for businesses, development of local crisis-resistant markets.

Climate migration and the preservation of cultural heritage

Resettlement leads to the disappearance of traditional communities and local customs.

Loss of language, rituals, customs, cultural fragmentation, change in the social landscape.

Solution: Documenting traditions, supporting local cultural initiatives, integrating migrants while preserving elements of regional culture, creating museums and educational programmes.

Podsumowanie

Climate migration is one of the most important challenges of the 21st century, combining environmental, social and political issues. Climate change is increasingly forcing people to relocate, both within countries and internationally. This process affects not only the lives of individuals and entire communities, but also the balance of power in international relations. Countries affected by the climate crisis are demanding support and solidarity, while countries receiving migrants are facing new integration, economic and social challenges.

In the future, climate migration is likely to increase, and its effects will be felt globally. It may become a source of tension and conflict, but also an opportunity to strengthen international cooperation and build new mechanisms of responsibility and support. It is therefore necessary to treat this phenomenon as an integral part of climate and migration policy today in order to effectively counteract its negative consequences and protect the most vulnerable communities.